Leadership comes in all forms, but for those with an interest in military history, leadership in war brings out very particular characteristics.

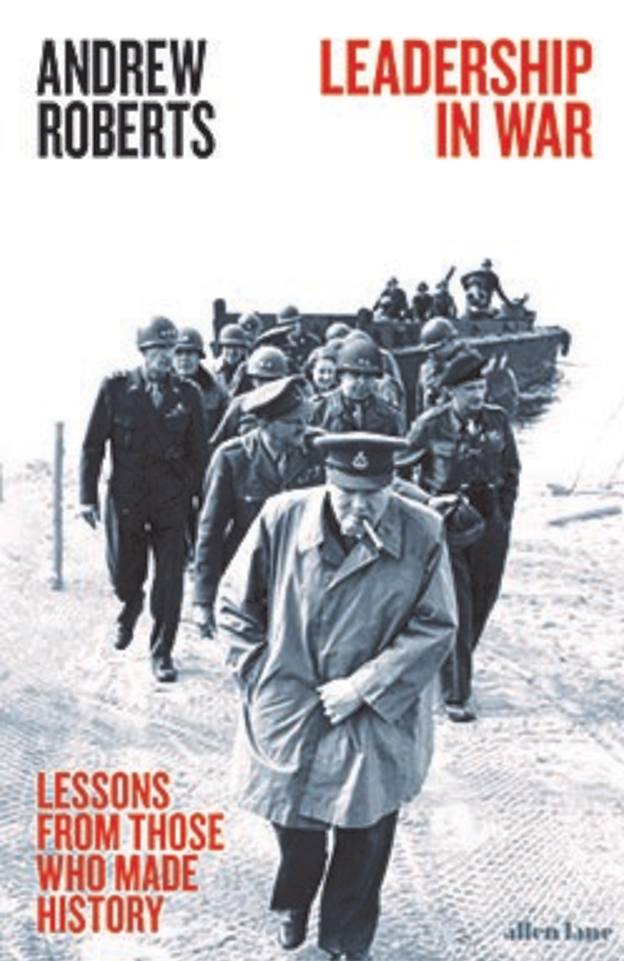

Andrew Roberts’ Leadership in War: Lessons from those who made history, gives an overview of nine very different leaders, all of whom experienced, and led in various fashions some kind of war.

For Margaret Thatcher it was the 10-week war of the Falklands, marked by her determination to see the conflict as an assault on British sovereignty and honour, while for Winston Churchill, it was his determination and battle for survival, helped not in short measure by many early brushes with death.

Each person is covered in turn: the book also includes Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler, as well as Napoleon Bonaparte and Horatio Nelson; but rather than being a detailed analysis of each leader’s military tactics, the book gives as much an idea of leadership style, as well as a brief summary of their greatest successes and failures.

Mr Roberts challenges the basic assumptions people may have: for example, Hilter was essentially lazy and mediocre at best, spending his time with his associates verbalising a stream of consciousness betraying his crazy thoughts (this has all been documented).

His ‘charisma’ was manufactured and he relied heavily on the talents of those around him.

Napoleon on the other hand was a genius who worked relentlessly, read widely and strove diligently to look after his army, and they backed him right to the end.

Mr Roberts, who has written a book about Napoleon, is convinced he did not have a “Napoleon complex”, and argues some of his biggest mistakes could not easily have been foreseen.

Leadership in War is clearly an exercise in understanding how different leaders, good and bad – Mr Roberts says leadership is ‘amoral’ - operate in times of extreme stress, which can be helpful for those in the corporate world also in leadership positions.

But he also raises the question of how people end up being led by these individuals: “How can 100 people be led by a single person?”

And more to the point, how can they stay in power? In the chapter on Stalin, he draws attention to the hundreds of thousands of people Stalin ordered to be killed – and killed himself – many of whom were picked at random, just to terrorise everyone else.

But despite this, the population still said: “If only Stalin knew what was going on.”

The answer says Mr Roberts was: “The plain fact is that over a decade of relentless totalitarian propaganda glorifying the leader worked.”

This is an interesting read for those who would like to know a little more about nine leaders, all of whom made their mark on war.

Melanie Tringham is features editor of Financial Adviser and FTAdviser

Published by Allen Lane