The government’s failure to subject itself to its own mortgage regulations has contributed to the plight of some mortgage “prisoners”, argues mortgage guru Ray Boulger.

A BBC Panorama programme has highlighted the predicament of former Northern Rock borrowers whose mortgages were sold to the government’s own bank, UK Asset Resolution, and private equity firms such as the US’s Cerberus, after the bank failed and was taken over by the government. The documentary focused on borrowers unable to move from their current lender, either because their circumstances had changed, or because their loans were considered unaffordable under the new mortgage regime.

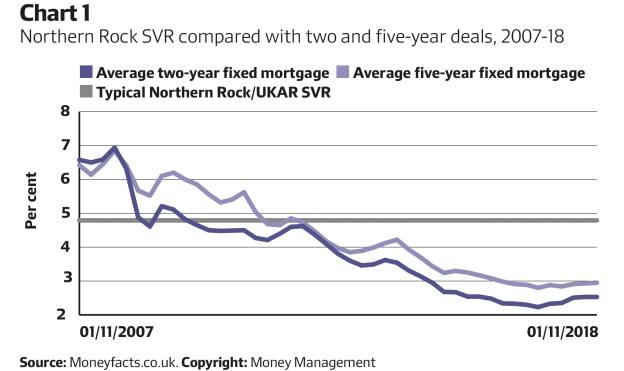

One expert on the programme suggested the borrowers featured were paying rates of around 5 per cent, in contrast to market norms of 1-1.2 per cent. It was estimated that one couple had paid an additional £20,000, and another an extra £30,000, over the past 10 years or so.

The problem is that these borrowers were probably not in a position to take advantage of competitive rates – Mr Boulger suggests many may be in negative equity, have obtained self-certificated mortgages before they were banned, or have interest-only loans with no means of repaying the capital.

Fair treatment?

The rules state that lenders are obliged to treat customers fairly and are not allowed to take advantage of customers just because they cannot remortgage elsewhere. But neither the government, UKAR nor any of the private equity firms involved are regulated by the FCA or subject to its TCF rules. That, says Mr Boulger, is not right. “The government should be setting an example of good practice,” he says. “By excluding itself from the mortgage regulations, I don’t think it’s done that.”

The regulator’s interpretation of the rules is that UKAR and the private equity firms are not allowed to offer changed terms and conditions to these borrowers. Mr Boulger says it should be assumed that customers who stayed with Northern Rock after its collapse are effectively a captive audience. The private equity companies are also likely to have bought the mortgage book on the basis that borrowers would stay with them on the same terms. Back in 2007, Northern Rock’s standard variable was at the higher end of the spectrum (around 4.79 per cent, as Chart 1 shows) and it offered 100 per cent loan-to-value mortgages. Two of the borrowers featured on the programme had taken out mortgages with LTVs of 110 and 125 per cent, respectively.

However, since 2013 the market has become increasingly competitive with lots of good product transfer deals available to good quality customers.

“This is about the disposal of mortgages to parties with no motivation to do anything about these mortgage prisoners,” says Robert Sinclair of the Association of Mortgage Intermediaries. He adds there are some in the industry who question whether the FCA’s interpretation of the rules is correct. Effectively, the rules state that the current lenders are not allowed to offer new deals to their customers, even if they wanted to. In addition, the stricter mortgage criteria in force prevent these prisoners from moving away. The application of stress tests and the need for lenders to restrict their proportion of borrowing above 4.5 times income to 15 per cent of borrowers are also likely to have exacerbated the problem.