Amid global lockdowns and uncertain recovery plans, economies, companies and individuals continue to face a wall of unknowns about the future.

The scale of Covid-19’s impact is profound across geographies, industries and asset classes, but the true extent of the damage — and the timeline for rebounds and recoveries remains unknown.

We have witnessed an immense, rapid and co-ordinated intervention in markets, easing the initial liquidity pressures seen in March.

Markets have been supported, calmed and caught out by these moves, and alarm bells continue to ring about when the reckoning may come.

Yet we remain cautiously optimistic about markets — and very optimistic about the potential to generate alpha in credit markets over the next 12 months.

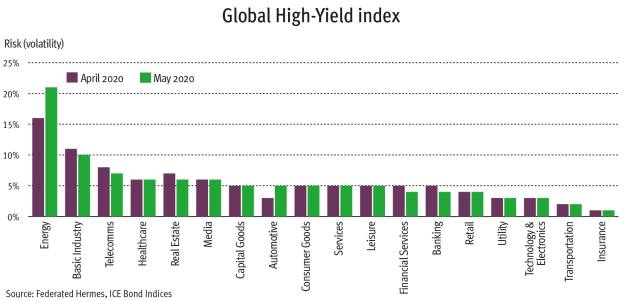

Recent market drama has been felt particularly acutely in the energy sector, where energy issuers were under sustained pressure even before the Opec and Russia failed to come to a supply-cut agreement in early March.

This development was cataclysmic for oil prices and hit North American producers and their support infrastructure extremely hard.

The current substantial imbalance between supply and demand may yet endure for several quarters.

If demand stays weak, markets could become oversupplied and storage capacity could be reached by Q3. North American producers with weak liquidity and balance sheets can now only hope for direct government support.

Bankruptcies within the sector have already started and we expect them to increase, irrespective of how markets recover.

This will have material implications for credit markets.

Energy now accounts for more than 12 per cent of the US high-yield market, a share that has recently increased with the addition of fallen angels — or credits downgraded from investment-grade status — to the index.

Five energy companies have moved from investment-grade to high-yield status, accounting for about $25bn (£20bn) in market value and 30 per cent of all fallen angels.

As a result, the high-yield index has become more polarised, concentrating investor focus on higher-quality names with larger capital structures, while lower-quality, distressed names have become less relevant.

Oil prices have declined by about 60 per cent year to date, which has implications for energy companies’ earnings, cash flow and fundamentally, survival.

Energy companies have responded proactively.

Exploration and production companies have reduced capital expenditure by 30 per cent, while businesses are limiting operating expenses and securing additional near-term liquidity through bank loans.

Dividends have been reduced or suspended, while midstream companies have cancelled growth capital projects and are reducing distributions.

Looking ahead, we continue to prefer midstream companies that lack direct exposure to commodity-price volatility, are protected through long-term or minimum-volume commitment contracts, and are able to postpone growth projects and reduce distributions.

We also like production businesses of scale with low break-even costs, strong balance sheets and good liquidity.

Natural-gas producers should also benefit as declining oil production reduces associated gas production, resulting in more normalised market dynamics.