As we begin a new decade, climate change is likely to be a prominent theme and, despite most countries having signed the Paris agreement, it is evident that we are not doing enough.

There are areas of progress. The UK is already generating more electricity from clean energy than its combined output from coal, oil and gas.

In December, the initial draft of the European Commission’s green deal was published. The commission’s deal is ambitious, and the bloc intends to be net zero from 2050.

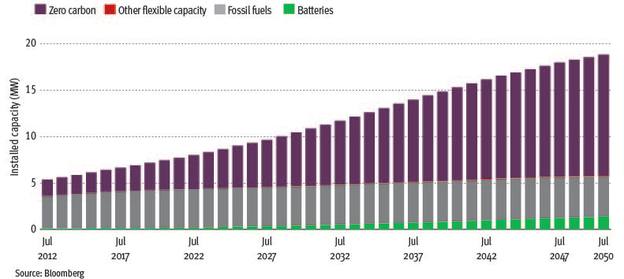

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that to be consistent with the 1.5C pathway, renewables need to make up 70 to 85 per cent of the energy mix by 2050 – up from 26 per cent today.

As governments around the world face up to the challenge of climate change, one thing is clear: clean-energy infrastructure will lie at the heart of actions to reduce global emissions (see chart).

Renewable energy: a clear opportunity

Advances in renewable technologies have driven down their levelized cost of energy – a generating asset’s total lifetime cost on a per watt basis – to lower than even the cheapest conventional generation assets.

Among these technologies, offshore wind has seen one of the steepest improvements in LCOE: the latest bids at UK auctions are around $50/MWh (£39/MWh), compared to global average generation of $175/MWh in 2015.

According to the International Energy Agency, offshore wind could become the number one power source in Europe by the 2040s, meaning the commission would meet its target of 230-450GW of installed capacity.

On a global scale, the IEA estimates that offshore wind capacity could grow 15-fold by 2040.

A number of European companies are capitalising on this move towards a clean-energy future and are prepared – and positioned to benefit – from a low-carbon world.

Orsted is the global leader in offshore wind, which has installed more than one quarter of the total offshore wind capacity globally. In September 2018, it completed the world’s largest offshore wind farm in the Irish Sea.

Another example is Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, which operates in the globally oligopolistic wind energy industry, where installations are set to rise nearly six-fold over the next decade.

As the installed base of onshore and offshore installations increases, services and maintenance become a bigger part of their business and will add meaningfully to earnings.

The move towards decarbonisation is also well underway in the automotive industry.

Cars are responsible for about 12 per cent of global CO2 emissions and manufacturers face increasingly stringent regulation.

The transition to a global electric car fleet will take many years and requires billions of dollars of investment in infrastructure and technology.

Automakers will also have to reduce the emissions of their existing internal combustion-engine fleet through the use of more effective catalytic convertors.

Global automotive production may be stagnant, but the increased cost of better ‘cars’ means we expect this segment, including companies such as Umicore, to grow.