For years, the UK has clung to its own currency and avoided joining the euro, on the basis of the pound’s strength and the euro’s apparent weakness.

How times have changed.

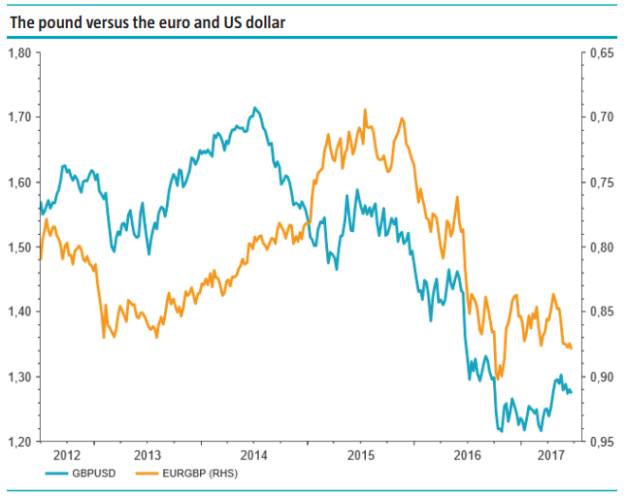

Since the referendum, the UK’s currency has fallen dramatically, hitting a 31-year low against the US dollar at one point last year.

There is little sign of it picking up in value, so long as uncertainty surrounding the negotiations for the UK’s departure remains.

The implications of the fall in sterling could be quite far reaching.

Léon Cornelissen, chief economist at Robeco Investment Solutions, says: “Sterling has always steadfastly remained outside the EU’s auspices after the UK’s repeated refusal to join the euro.

“Pro-Brexit commentators had long mocked the euro as being susceptible to the long-running economic sagas of the eurozone, leading to bailouts for Greece and the largest European quantitative easing program in history. Some doubted whether the euro would even survive.”

Figure 1: The pound versus the euro and US dollar

Source: Robeco Investment Solutions/Thomson Reuters Datastream

But he observes: “Now, the boot is firmly on the other foot.

“After the Brexit referendum the pound weakened about 12 per cent vis-à-vis the euro and the US dollar, as investors concluded that leaving the largest internal market in the world would probably be a structural headwind for the UK economy.

"The pound fell another 1.5 per cent after the Conservatives failed to win an overall majority in the 2017 snap election and is seen weakening further in the absence of a trade deal to replace membership of the single market.”

Inflation looming large

Some of the biggest beneficiaries of this decline in the pound have been companies which export their goods or services, and this is why the FTSE 100 has received such a boost in the aftermath of the referendum.

The majority of businesses in the index generate a significant amount of their revenues overseas, and as a result have been able to take advantage of sterling’s drop.

However, imports into the UK are being hit and this is feeding through into higher costs for many food items, for example.

Higher food and fuel prices mean a higher rate of inflation, which hit 2.9 per cent in May, only to come back down to 2.6 per cent in June.

As Mr Cornelissen points out: “Real incomes are now declining, as British workers are not compensated for the rise in inflation with pay rises, due to companies remaining cautious amid the increased economic uncertainty.

“This has also been true of public sector workers, who have also been declined pay rises that mirror rising inflation, as the government reins in its spending.”

In other words, spending power is being eroded and not that slowly either.

While some feel this could help the UK’s balance of trade, Will Hobbs, head of investment strategy at Barclays Wealth and Investments, is not convinced.